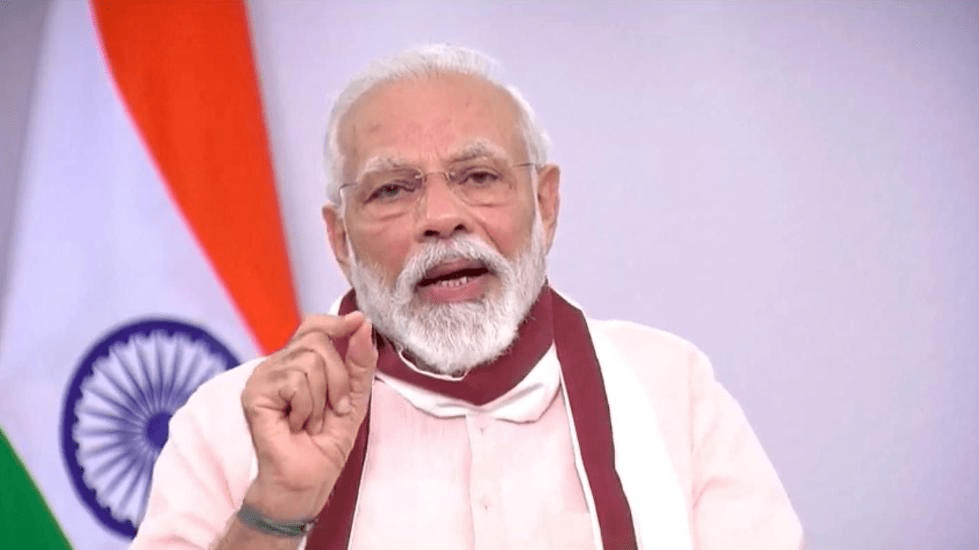

As a “strong government”, how many concessions can the Modi government make in the end if it insists that “agricultural reform will give farmers more rights and opportunities”?

“If the government cannot rescind the AG bill, we will launch a nationwide protest on the 14th.” Indian farmers who took to the streets to protest again challenged the Modi government this weekend.

Since late November, the Indian government has held several rounds of negotiations with farmers, but consensus has not been reached.

Although Tomar, the minister responsible for India’s agriculture, rural areas and farmers, said that the government is willing to amend the new bill to dispel farmers’ concerns, it remains to be seen whether the latter will “stop tearing the government” as he wishes.

The Modi government originally wanted to break the unified purchase and sale of agricultural products and the inherent interest pattern of intermediaries, so that farmers could directly contact the market, but Indian farmers who were worried about losing the “protection layer” were not appreciating.

Why have Indian farmers taken to the streets to protest repeatedly over the years?

Why is this protest supported by overseas Indian expatriates and some Western dignitaries? In the final analysis, the peasant march into New Delhi reflects India’s “agriculture, rural areas and farmers” dilemma.

Why are there so many protests, suicides and “onion crisis”?

Since November 26, Indian farmers have held protests in the capital, New Delhi and other places, despite the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic, against the government’s three agricultural reform bills – the Agricultural Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, the Farmer (Authorization and Protection) Price Guarantee Agreement and Agriculture.

Services Act Basic Commodities (Amendment) Act. According to Tomar, India’s minister in charge of agriculture, rural areas and farmers, “These bills are historic and will make a difference in farmers’ lives.

Farmers will be able to freely trade their agricultural products anywhere in the country.” However, farmers asked the government to repeal the above-mentioned bill and continue to maintain the current guaranteed “minimum support price” system.

Tens of thousands of farmers headed for the capital New Delhi. They built protest camps and blocked highways on the main roads entering the city. During this period, Indian police clashed physically with protesters, and even used tear gas and water cannons.

Similar farmers’ protests have often occurred in India in recent years, but on a large scale and small scale, with a variety of demands.

In August 2017, half a million farmers in India entered Mumbai, the economic center, to hold a protest. In the background, in addition to expressing dissatisfaction with rising unemployment and falling agricultural incomes, farmers also demanded that their allocation of places for employment in government agencies and university attendance were guaranteed.

In March 2018, Indian farmers entered the Mumbai demonstration again. More than 30,000 farmers from Maharashtra held up red flags, demanding forgiveness of loans and raising agricultural prices. In November 2018, tens of thousands of farmers protested in front of the parliament building in New Delhi to protest against the agricultural policies of low food prices and export restrictions implemented by the Modi government.

Indian media reported that the relevant policies have caused farmers’ operating costs to soar and food prices to fall, which directly led to the decline of farmers’ living standards.

In addition to the demonstrations normalized by farmers, there are two phenomena in Indian agriculture that deserve attention: the increase in the number of suicides by farmers and the continuous “onion crisis”.

In 2019, 10,281 farmers committed suicide, compared to nearly 300,000 Indian farmers from 1995 to 2014. Onions are indispensable ingredients for Indians in their daily life. Every time the price of onions rises, it will cause strong dissatisfaction among the Indian people.

India owns one-tenth of the world’s arable land and is the world’s largest food producer. In the world’s second largest population, the rural population accounts for 72% of the total population.

But electoral politics and industrialization have put Indian farmers in an increasingly holistic crisis situation. The current Indian peasant demonstrations have also attracted the attention of European and American politicians and the media, and expressed “concerned” about the way the Indian government responded to the protests.

The New York Times commented that the COVID-19 epidemic and economic contraction have already caused Modi’s government a headache, and the anger of nearly 20 days of farmers’ demonstrations has further exacerbated the plight of Indian rulers. CNN related reports that Indian farmers protested against the new agricultural bills because they believed that they destroyed their livelihoods.

“If we lose the ‘minimum support price’ and without this layer of protection, companies can easily buy out our produce,” said farmers from Uttar Pradesh. “It will make our situation even harder.” “It’s like ‘big fish eat small fish,’ big business groups will eat Indian farmers,” Lax, a farmer protesting farmer in New Delhi, told British media.

According to India’s “Wire” network, trucks have been delivering rice, flour, vegetables, white sugar, tea and other food to protesters in recent days, and nearly ten tons of almonds have been brought recently.

Par Singh, a Punjab farmer, said: “The food comes not only from India, but also from Britain and Canada. We don’t have food shortages and we have enough food to last for months.”

It is reported that the protracted peasant protest was also supported by Indian Sikh communities from Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and other countries, who held demonstrations in populated areas and in front of Indian embassies and consulates.

The U.S.-based Sikh Justice Organization even threatened to “close” some consulates in India to support farmers.

Why are you worried about losing the “protection layer”?

What does the Modi government’s agriculture bill change? Why did it cause such a large-scale rebound among farmers? In fact, what the Modi government wants to change is India’s unified purchase and sale policy of agricultural products.

Driven by social equity and electoral factors, successive Indian governments have also made efforts to protect the interests of farmers and intervene in Indian agricultural prices. In order to stabilize food prices and ensure the food supply of low-income groups, all grain sources controlled by the Indian government control prices from both acquisition and sales.

The control price of the acquisition link is called the “minimum support price”, and the control price of the sales link is called the “central unified pricing”.

“Minimum support price” is based on the Agricultural Cost and Price Committee of the Ministry of Agriculture based on farmers’ production costs, price trends in domestic and foreign markets, price differences between harvest seasons, supply and demand, possible impact of “minimum support prices” on consumers, international market conditions, agricultural trade cycle, agricultural products and non- The terms of trade in agricultural products, the cost of farmers and their livestock cultivation, and the profits of growing grain should be studied and determined, and formulated once a year.

The price of centrally controlled food distribution and sale to the states is set by the central government of India, specifically determined by the central government of India and the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. This price is the central unified pricing.

These measures play an important role in safeguarding the interests of farmers, but this method of unified purchase and sale also greatly limits agricultural development. Such as breeding corruption, the emergence of trade intermediaries, etc. According to Indian media analysis, Modi’s government is to remove intermediaries and let farmers directly connect with the market.

These middlemen have formed a strong lobbying group. They often gamble on the agricultural market, and the prices of agricultural products fluctuate and fluctuate. Moreover, since the establishment of the Agricultural Production Market Commission of India in 2003, farmers’ all agricultural products have to be sold to designated government acquisition agencies, which has spawned a large number of customers who are the coordinators and communicators of farmers and traders, weakening or even losing their ability to bargain and finance agricultural products.

In addition, in recent years, the huge fiscal deficit caused by agricultural subsidies and the decline in the global competitiveness of India’s agricultural products are the original intentions of the Modi government’s agricultural reform bill.

For example, in FY 2014-2015, the price of wheat in India was much lower than that of most competing countries: the price of wheat in India was $330 per ton, compared with $580 in Thailand.

Seeing these shortcomings, Modi’s government wants to solve the problems caused by these protective measures through market-oriented reform, liberate from the Congress Party’s excessive protection of farmers, and use market-oriented means to open up the link between farmers and the market. However, long-term protection has made farmers inertial at protection prices. Unprotected farmers are afraid and afraid of the uncertainty brought about by the market, and can only strengthen this protection mechanism through demonstrations.

The Indian Express quoted “intelligence community sources” as saying on the 11th that the protest was “kidnapped” by vested interests, and some far-left and pro-left extremists took advantage of farmers’ anger to fuel the fire, and they may want to encourage farmers to resort to violence and arson to vent their dissatisfaction.

At the same time, opposition parties are indispensable behind the Indian farmers’ protests. According to the Indian Newspaper Trust, the Congress Party and the People’s Party will join the farmers’ protests in Punjab on the 14th.

The two parties will hold state and district protests respectively. They said that “the voice of farmers’ voices should be heard by the central government enough”. There are also opposition parties who believe that Modi actually “only cares on the votes in the hands of farmers”.

How many concessions can a “strong government” make?

The Indian scholar Yadav divided the modern Indian peasant movement into three stages. The first stage was a peasant uprising and protest demonstration against the British colonists.

The second stage of the peasant movement emerged in the late 1980s. The main body is rich farmers who have obtained a small amount of land after land reform or whose situation has improved due to land reform. They face marginalization in rural economic development and modern industrial economy. The main demands are agricultural product prices and migrant workers’ salaries.

They are landless farmers and large landowners. Forced struggle. The main body of the peasant movement in the third stage is the peasant radicals since the economic reform. At this stage, India’s agricultural development is facing difficulties.

Farmers are impoverished, the agricultural economic and ecological crisis is turning into a peasant survival crisis, and farmers’ suicide and protests caused by the “onion crisis” are all corresponding manifestations.

According to Indian media reports, the All India Farmers Coordination Committee, which has nearly 200 farmers’ organizations, has launched many farmers’ protests in recent years. In India, people in several states also went on strike to cooperate with farmers’ protests.

The Indian Tribune also commented that the third stage of the peasant movement was removing the existing line between landlords, farmers, landless farmers, etc., and rural poverty forced them to unite to fight resistance and demonstrations.

Traditionally, Indian Dalit class is one of the main groups of migrant workers, but mainstream farmers do not include them in agricultural activities and are not regarded as farmers. But now this trend is changing, and the peasant movement is more willing to involve Dalits and rural women.

In addition, the widening urban-rural dual divide in India has made farmers rethink: Does the neglect of the modern economic system and the ecological crisis plunge farmers as a whole into an existential crisis? Perhaps this is the first time that all farmers’ organizations in India have reached agreement on a common issue: demanding fair and reasonable agricultural prices and forgiveness of farmers’ debts from the government.

The New Farmers Movement demanded that the government compensate for the price of agricultural products, and the actual price of agricultural products paid was the same as the price announced by the government, and also demanded that private lenders get rid of the debt trap.

In fact, India’s central government invests a lot in rural areas every year. Between fiscal year 2006-2007 and fiscal year 2011-2012, the proportion of social services and rural development in India’s central government’s fiscal expenditure increased from 13.4% to 18.5%, but the rural poverty alleviation effect was poor.

Previous governments have made little progress on the issue of agriculture, rural areas and farmers, and political parties were more Shout slogans. In 2014 for the general election, Modi’s BJP promised to give “the highest priority to agricultural growth, farmer income and rural development” and proposed specific figures to take measures to improve agricultural profitability and ensure that profits exceed at least 50% of production costs.

There were many commitments during the Modi election, such as: increasing the “minimum support price” of agricultural product acquisition by 50% after taking office; increasing investment in agriculture and rural development; providing medical security and more agricultural insurance for smallholders over 60 years old, marginal farmers and migrant workers; reforming the Agricultural Production Market Committee in the country and state Set up “Land Use Bureau”, seed laboratory, etc.

However, after Modi came to power, most of these measures were not implemented. Some policies and legislation replaced old policies and laws with new names, and farmers, landless farmers and rural women continued to be excluded from agricultural credit, food purchase price support systems, crop insurance and various subsidies.

The federal government has more stricter than before on subsidies for food purchase support prices. In February 2015, the federal government said in response to the Indian Farmers Association’s application for a 50% increase in the “minimum support price” for agricultural acquisition, “this may be against the market (rules).”.

In the face of criticism from all walks of life and the BJP’s defeat in the elections in five states, including Rajasthan in December 2018, the Modi government has begun to urgently remedy again – the 2019/20 budget is heavily tilted towards rural areas and farmers.

Before the 2019 election, Global Times reporters interviewed the rural state of Haryana, which is adjacent to the capital of India, and has some understanding of the current situation in rural India.

In a village called Yot Village, Master Singh, who is responsible for public welfare and rural development of the village, complained: “Eight years ago, the government gave a large discount when farmers bought seeds and fertilizers, but now the government has cancelled the discount.

Now the government wants higher agricultural electricity bills. Singh also said at the time: “The current government does not support farmers. The original government would give farmers various insurances, including floods and natural disasters, but now these insurances have been cancelled.

However, the reporter also saw some Indian media analysis that “agricultural subsidies increase the financial burden of the country and compress the space for agricultural investment”.

The Global Times reporter was also impressed by the film Wrestling! Influenced by Dad, wrestling training venues have been built in two villages visited by the reporter.

Villagers also attach importance to the education of girls, and some women’s skills training centers, such as teaching women sewing. In the village of Yote, two female students in school uniforms are also painted on the school gate. It is understood that the village school is exempt from all fees for students, including textbooks, tuition fees, uniforms, etc., and there is a free lunch at noon.

No wonder, in the procession of Indian farmers’ demonstration, some farmers put pressure on the government with slogans “We are educated farmers”. But as a “strong government”, how many concessions can the Modi government make in the end if it insists that “agricultural reform will give farmers more rights and opportunities”?