With winter approaching, Sweden’s coronavirus epidemic is in danger again. The number of new cases in Sweden has been climbing into November.

As of December 13 local time, the cumulative number of confirmed cases and 7,500 deaths in the country has exceeded 3,500.

The intensive care unit (ICU) in the capital Stockholm reached its limit last week.

Under heavy pressure, Swedish health officials begged the public to abide by epidemic prevention regulations, and Stockholm health officials openly asked for help.

Under the huge pressure of work and relatively low wages, there is a wave of resignations for Swedish medical staff.

According to Bloomberg on December 12, Sineva Ribeiro, president of the Swedish Association of Health Professionals, said that Sweden faced a shortage of medical staff at the beginning of the outbreak of the coronavirus in March this year, and after a year of “relentless” epidemic, more and more medical personnel The shortage of personnel increased due to the resignation of personnel.

Ribeiro said union members warned her back in May that the coronavirus pandemic was “not in a good situation” and that fewer qualified medical staff today than in the spring, especially in the intensive care unit.

Many healthcare workers are increasingly “desiring for a real vacation” under heavy pressure, so they regard resignation as the “only way out”.

On the other hand, the relatively low salary of medical staff is also the reason why they want to resign.

An ICU assistant nurse named Sara Nordin told Bloomberg that she resigned because she could not make ends meet on a base salary of $33,600 a year.

According to a data from the Swedish TV4 Broadcasting Corporation, the number of resignations in the medical industry in 13 of Sweden’s 21 counties this year has increased compared with the previous year, with an average of 500 resignations per month.

According to Sweden’s national television (SVT), about 3,600 health workers in Stockholm have resigned since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, about 900 more than the same period last year.

Ribeiro on the dangers of resigning: “The danger for Sweden now is that more people will die because there are not enough qualified medical professionals to take care of them.”

Irene Nilsson Carlsson, senior public health adviser of the Swedish National Health and Welfare Council, defended to the Financial Times: “We are worried about the situation, but we are not worried that it will get out of control.

The atmosphere in the intensive care unit is tense and the staff is very heavy. But we can expand the current capacity, so it’s not a serious crisis.”

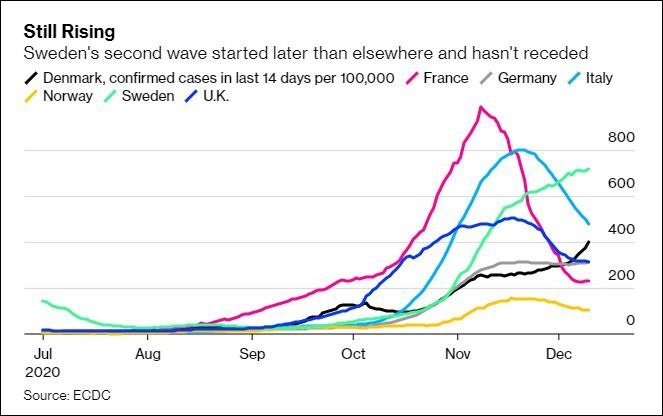

According to Bloomberg statistics, Sweden’s number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 people has been rising sharply in November compared with neighboring countries. On December 8 alone, 18,820 cases were diagnosed.

As of December 13, the cumulative number of confirmed cases in Sweden has reached 32,08, and the number of deaths has reached 7,514.

The capital Stockholm and its surrounding areas are the hardest hit, with 2,836 deaths. After a calm in the summer and fall, infection rates are beginning to pick up again, and ICUs are now full. Last Wednesday (9th), the Stockholm area had 99% occupancy in intensive care units, near the limit.

This also led Bjorn Eriksson, the head of the Stockholm regional health department, to hold a press conference and openly ask for help from the outside world to call on the state to send professional nurses and other hospital staff.

At present, although Sweden has not officially turned to foreign countries for help, neighboring Finland and Norway have indicated that they will provide medical assistance to Sweden.

“We have not received an official request for help, but we will assess the situation in the hospital every day, and of course, we are ready to help Sweden where possible,” said Kirsi Varhila, an official of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland, told the Swedish media.

Maria Bjerke, a Norwegian Ministry of Health official, also told the Norwegian National Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) that there is a cooperation agreement between the Nordic countries that allows for the sharing of medical assistance in a short period of time. If Sweden asks us for help, we will take a positive attitude.

However, Johanna Sandwall, director of emergency preparedness of the Swedish National Health and Welfare Council, said on the 13th that Sweden did not plan to seek help from neighboring countries. “The health care situation in several regions of Sweden is very tight, but we have the ability to immediately meet the needs of the whole country,” she said.

In the face of a surge in new cases in recent weeks, the Swedish government has tightened restrictions on public gatherings, while requiring high schools to switch to remote teaching for the rest of the semester, but these have circumvented legal restrictions and are only guidance recommendations issued by the government.

Currently, the Swedish government is working on an epidemic emergency law that allows the government to close shops and restrict the use of public transportation, but the law will not take effect until mid-March.

This month, when the traditional Christmas of the West approaches, Sweden is facing another wave of epidemic prevention pressure. In response, Erickson, the head of the Stockholm regional health department, appealed to the public not to drink, go shopping at Christmas or meet people outside their families after work, because “the consequences are terrible” and it is not worth it.