While many countries in the United Kingdom, the United States and the European Union are excited by the coronavirus vaccination, there are still some countries in the world who can’t get a vaccine for a short time.

The New York Times’ December 28 issue pointed out the root cause of this phenomenon, that is, global wealth inequality is affecting the priority of many countries to obtain vaccines.

In the past few months, rich countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada have reached agreements with many pharmaceutical manufacturers and ensured enough doses to inoculate people multiple times.

However, countries like South Africa are in a special dilemma: they are “too rich” – they are not considered eligible to get cheap vaccines from international aid organizations; they are “too poor” – they can’t compete with rich countries to order vaccines.

This “not going up” makes them hopeful of getting a vaccine as soon as possible.

“These countries are too rich and too poor to get a vaccine”

In this report co-written by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Matt Apuzzo and investigative journalist Selam Gebrekidan, the two journalists take the perspective of South Africa to show some middle-income countries in the vaccine score.

The awkward situation on matching.

“If you’re not rich enough, but not poor enough, you’re going to be in trouble.” Salim Abdool Karim, head of the South African Covid-19 Advisory Council and epidemiologist, said.

On the one hand, “money is turning into an undeniable advantage”, and low- and middle-income countries are basically unable to compete with rich countries in the open vaccine market.

According to the report, from the beginning, the South African government knew that the country could not order vaccines like rich countries until the vaccine was tested and approved.

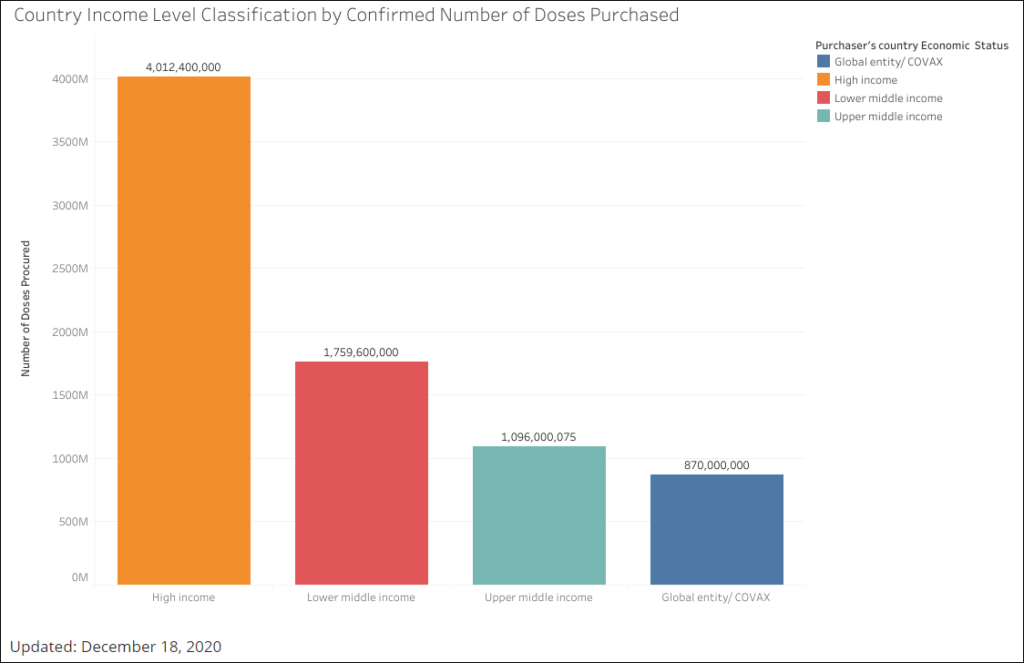

The latest data from the Center for Global Health Innovation at Duke University in the United States proves this.

According to statistics, before the candidate vaccine was approved for market, there were 7.7 billion doses of confirmed global procurement. And most of the vaccines go to high-income countries.

Specifically, as of December 18, high-income countries have now confirmed to hold 4 billion doses; upper middle-income countries hold 1.1 billion doses; and lower middle-income countries hold 1.8 billion doses.

As for low-income countries, Duke University has not found evidence that these countries have reached any direct agreements with pharmaceutical companies.

“We haven’t even started shopping yet when we’re shopping spree in these countries.” Ames Dhai, a professor of bioethics and a member of the South African government’s vaccine advisory group, told doctors in a recent webinar.

On the other hand, these countries in South Africa are still “not able to have hope for philanthropy”.

Apuzo and Gebrekidan pointed out that although the South African government was almost bankrupt and half of its citizens lived in poverty, South Africa was considered too rich to qualify for a cheap vaccine from international aid organizations.

In addition, the situation in South Africa is also mixed among the COVID-19 Vaccine Implementation Plan (COVAX) project to promote equitable distribution of vaccines worldwide.

According to the report, although joining the project can enable South Africa to obtain vaccines, unlike subsidized low-income countries, South Africa in middle-income countries can only pay an advance of about $140 million as a “self-of-pocket economy” to purchase vaccines from COVAX for about 10% of its population.

Unable to know what vaccines will be obtained from the COVAX project and when to get it, South African medical advisers said that although the COVAX project is crucial, these circumstances are also deeply frustrated.

“In South Africa, people’s best chance of getting a vaccine is to participate in trials”

So, can South Africa, which has more than one million people infected with the novel coronavirus, have to wait? The report pointed out that people actually have the “best chance” to get a vaccine, but this situation may be “heartbreaking”.

“The best chance for many South Africans to get a vaccine in a short period of time is to volunteer to participate in clinical trials and test unproven vaccines on them.” Apuzo and Gebrekitan wrote.

As the UK prepares to launch vaccinations, dozens of people walked from their shacks to Desmond Tutu Health Found in the town of Masiphumelele in southern Cape Town, South Africa this month. The door of ation.

They waited for hours in the shade of a tree outside, just to have the opportunity to sign up for the clinical trial of Johnson & Johnson’s coronavirus vaccine candidate.

“Maybe we will get the vaccine by 2025,” Mtshaba Mzwamadoda, 42, sarcastically said. He lives in a one-bedroom hut with his wife and three children. Prudence Nonzamedyantyi, 46-year-old housekeeper from the same town, said, “But then, we are all dead.”

“That’s why we signed up,” Mzwamadoda said. “That’s the only chance I have [to get a vaccine].”

Katherine Gill, who led the trial, further noted that people would not have access to any vaccine anytime soon unless they were exposed to a vaccine study, which was “clearly heartbreaking”.

The reason why South African people were able to sign up for clinical trials of Johnson & Johnson vaccine is that Aspen Pharmacare, a domestic pharmaceutical company, has signed a million dose vaccine production agreement with Johnson & Johnson & Johnson in the United States. But since South Africa did not pre-order vaccines from pharmaceutical companies, the country may have to watch Aspen produce vaccines for other countries first.

As described at the beginning of the article: Millions of doses of vaccines in South Africa’s factories may be shipped to a distribution center in Europe and then rushed to Western countries where hundreds of millions of orders are already made, where “no dose of vaccine is reserved for South Africa”.