Since the outbreak of the coronavirus epidemic in the United States, the Trump administration’s response has been widely criticized. Recently, after the emergence of mutant COVID-19 cases in the United States, the U.S. media noticed another major flaw in the domestic epidemic response – virus gene sequencing.

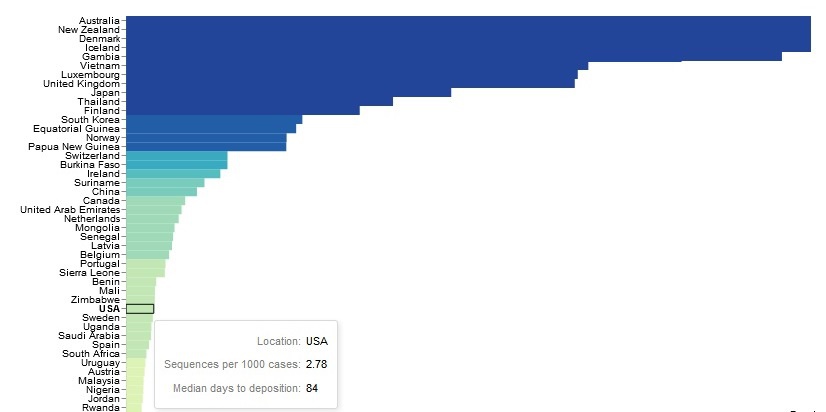

According to the virus database GISAID, the United States lags behind many countries in terms of both the proportion and speed of virus gene sequencing, according to the virus database GISAID.

Many countries that lag behind the U.S. medical resources, such as Bangladesh, Suriname and Sri Lanka, process virus samples faster than the United States.

In response, medical experts thought it was “sad” and could cause the widespread spread of new virus variants in people, but the government did not know about it.

Moreover, experts also worry that this may cause the vaccine to fail.

In terms of sample processing speed, the United States is lower than Suriname.

According to GISAID data, the United States ranks 61st in the world in terms of the speed of collecting, analyzing and publishing virus samples from patients.

Many countries with much less medical resources, including Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Suriname, process samples faster than the United States.

Regarding the backwardness in the sequencing of virus genes in the United States, Dr. Peter Hotez, a virologist at Baylor College of Medicine, said: “This is sad.

When you have to wait 85 days, a gene sequence may have gone from a rare mutation to a virus that is popular in half the population.

“When many countries are doing better and obviously better, I think it tells us that the United States should work together,” Nancy Cox, former director of the CDC’s influenza department, said.

Dr. Gregory Armstrong, director of the CDC’s Office of Advanced Molecular Detection, argued that the data on GISAID were delayed and therefore “misleading”, but he also admitted that the United States “still needs to improve” in virus gene sequencing.

“In the United States, CDC laboratories, national health departments, private companies and universities are submitting sequences to GISAID,” Armstrong explained.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that the test turnaround time (TAT, the time when the indicator book was collected to the laboratory received specimens) was not important.”

However, CNN pointed out that the United States has been criticized for virus gene sequencing, not just because of time delay. Given the “rampy” of the virus in the United States, there are too few cases of gene sequencing in the United States.

The United States has mapped and published nearly 70,000 samples of COVID-19 infections, second only to the 150,000 in the UK, according to GISAID data. However, the United States has more coronavirus cases than any other country, and now exceeds 22 million cases, far more than the rest of the world.

Therefore, in terms of the proportion of sequencing, the United States has been deficient. According to GISAID data, only 2.8 gene sequences are published in the United States for every 1,000 cases, lag behind 34 countries.

In absolute proportion, the number of gene sequencing cases in the United States accounts for only about 0.3% of the total cases, ranking 43rd in the world.

GISAID’s latest comprehensive ranking of data: 2.78 cases per 1,000 cases in the United States, with a median test time of 84 days

At the end of last year, about 3,000 samples were sequenced in the United States every week. Earlier this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention set a target to increase the number of samples released by laboratories in the United States to 6,500 per week within two weeks.

Armstrong said that the week from January 2 to 8, the U.S. laboratory sequenced 10,619 samples, but only 1,001 of them were collected in the past four weeks.

In response, Cox said pessimistically: “Do we have to be at the bottom of all things related to the COVID-19 epidemic, or close to the bottom? I know we could have done better but didn’t do it, which was really frustrating.”

Expert: Gene sequencing is the key, which may affect the vaccine.

William Haseltine, a professor of public health at Harvard University, wrote in Forbes on January 8 that gene sequencing is the key to identifying viral mutations.

If the sequencing is not good enough to identify new strains, not only the prospect is terrible, but also the use and promotion of vaccines. It will be affected.

Hasserdin Cope said that the essence of genome sequencing can obtain the base order of DNA molecular chemistry. Scientists use these sequences to identify genes, monitor instructions, and in the case of COVID-19, they can recognize viral mutations.

The sequencing work in the early days of the epidemic helped scientists determine the structure of the virus and make people realize that the virus is infectious enough. Recently, sequencing has also helped people identify two mutant viruses in the United Kingdom and South Africa.

For nearly a year, the Covid-19 Genomics Consortium has been tracking changes in the virus, recording more than 150,000 virus samples.

But in the United States, gene sequencing is very lagging behind. New strains have emerged in the United States from the United Kingdom and South Africa, and this spread shows that cases involving these mutant viruses are already very common.

However, the lack of genome sequencing in the United States makes the mutation evade monitoring.

Hasedin pointed out that the virus may mutate every time it spreads to a new host. There are tens of millions of recorded cases around the world, so there may be new hidden strains that have not been found.

Some estimates suggest that between 15-20% of Americans in the United States alone have been infected with the novel coronavirus, making it possible for the case in the United States to derive a new variant. If the native variations are present, this may help explain the recent surge in COVID-19 cases observed during the holiday season.

The prospect of a more infectious strain spreading in the United States is terrible enough, but if there are enough mutations, a strain may ineffective the current vaccine, which is why efforts to find these new strains must be intensified.

If a portion of the population has a COVID-19 vaccine-resistant strain, the national public health agency must identify them and continue vaccine research on this basis.

Finally, Hasedine said that vaccine distribution is now moving forward and life may return to normal in 2021, but the opposite may also happen.

The United States and the world must strengthen the sequencing of virus genes, identify and isolate new strains. Otherwise, mankind will still face a very long year.