India’s cultivated land area is 1.891.7 million square kilometers, accounting for 57% of the land area. In the world’s second largest country, the rural population accounts for 72% of the total population.

Although India’s industrial and agricultural production has developed rapidly, its agricultural-dominated industrial structure has not changed. Since the 13th century, Indian agriculture has been following the “intermediary acquisition model”, that is, the government’s agricultural freedom committee decree, which mainly divides India into more than a thousand regions according to provinces and regions. Farmers must first sell their agricultural products to the “agriculture” set up by the official government.

Under the product market, the acquirer, that is, the “intermediary”, is then resold to large distributors by these intermediaries. All farmers cannot sell grain across the district. That is, farmers in the region can only sell their own wheat to the buyers in the region. Even if the purchase price of wheat in the next district triples, farmers are not qualified to sell wheat across districts, otherwise it is illegal.

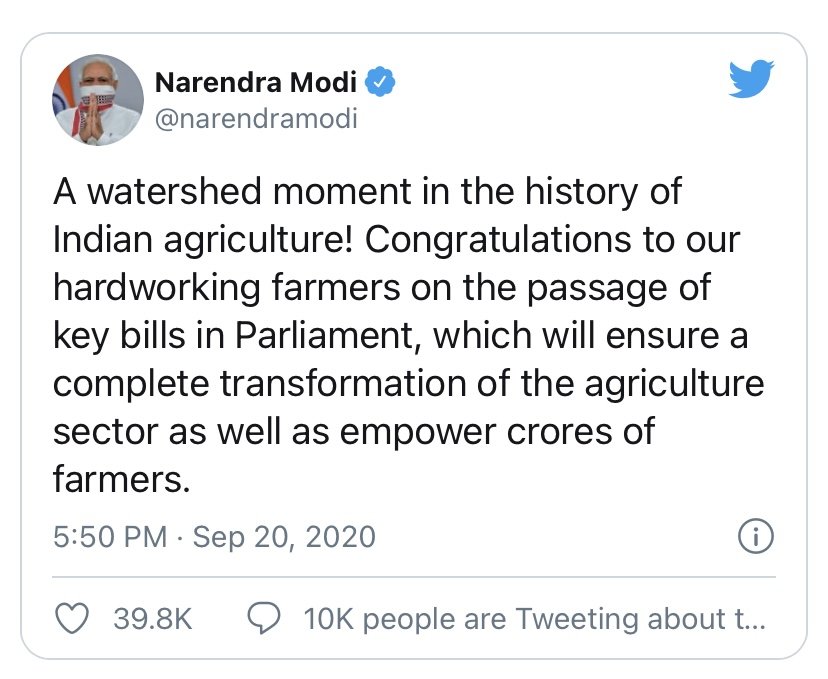

Until this year, the decree was repealed and Modi announced new agrarian reform. In September, the Indian government passed three agricultural reform bills: the Agricultural Trade and Commerce Act (Enhanced and Promotion), the Farmers Price Guarantee and Agricultural Services Act and the Necessities (Amendment) Bill.

The new bill mainly includes: abolishing the “intermediary system” and allowing farmers to trade directly with large distributors; giving farmers and various operators the right to sign pre-sale contracts to sell unharvested agricultural products at a pre-negotiated price.

In short, the production and sale of agricultural products are no longer traded through intermediaries, but directly by farmers with institutions and even individuals. This means that Indian farmers will lose the guarantee of the minimum purchase price set by the government.

Minimum Purchase Price Guarantee (MPS) is the corresponding minimum purchase price (150% of farmers’ planting costs) for some crops annually according to the calculation of the Agricultural Cost and Price Commission to protect the interests of farmers.

Starting from November 26, tens of thousands of farmers dissatisfied with the agricultural reform drove tractors to New Delhi, the capital of India. In just a few days, the number of protests has reached nearly 300,000, and the protests have continued to this day.

Modi: The purpose of implementing reform is to “open the door to a new world”

According to Modi himself, the core of this agricultural reform is to “give farmers corresponding freedom”.

The Modi government claimed that through agricultural reform, “intermediaries earn price differences” can be avoided, and Indian farmers can directly connect with the market, thus obtaining more profits.

Modi said that the new bill aims to protect the interests of farmers. In his public speech, he cited a maize grower in Maharashtra as an example. He said that before the implementation of the new agricultural bill, the farmer did not receive payment for the sale of corn for four months.

However, under the new bill, if the payment is not received three days after the sale of agricultural products, farmers can directly file a complaint.

For a long time, in order to protect the income of Indian farmers, the Indian government has been implementing agricultural subsidies, which has also put great pressure on the government’s finances.

From 2018 to 2019, the agricultural budget reached 5.76 trillion rupees, while the total revenue of the central treasury was about 20.8 trillion rupees. At present, due to the continuous spread of the COVID-19 epidemic, the cumulative number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in India has exceeded 10 million.

India’s economy has also been hit hard. India’s economic growth fell 7.5% year-on-year in the third quarter of this year. For two consecutive quarters, the economy experienced negative growth and the economic growth rate fell to its lowest level since independence.

In this case, agricultural subsidies have become “unaffordable” for the Indian government.

Modi believes that India’s agricultural system has seriously dragged down India’s industrialization process, and a large number of people have been “tied” to land. Modi’s government planned the so-called “Kangzhuang Avenue” for India: accelerate the industrialization process and become a major manufacturing country.

In order to achieve this goal, Modi has carried out reforms, unified the tax system, built smart cities, and vigorously introduced foreign capital in China.

However, in the modernization process, farmers and agriculture have been forgotten.

Apart from making welfare promises to farmers at the election, Modi’s government has launched few substantive measures to improve the situation of farmers in the past six years, and the promised benefits have been empty.

In a large country where more than half of the population is engaged in agricultural production, a series of reform policies of the Modi government ignore the excessive dispersion of the peasant group and the lack of independent bargaining power, while depriving farmers of the minimum livelihood security, thus triggering the peasant group to rise up.

The wave of opposition is getting stronger and stronger.

Since late November, groups of Indian farmers have been driving tractors, carrying daily necessities and food to protest in the streets of New Delhi and clash with the police.

So far, the wave of protests has not weakened, but has intensified.

On December 8, protest farmers launched a nationwide “All India Strike”, which was supported by many opposition parties, trade unions and industry associations.

In addition to a large number of Indian farmers who opposed the agricultural reform bill, opposition parties such as the Indian National Congress Party also expressed opposition. In September this year, on the day Modi voted on the agricultural reform bill, several opposition parliamentarians protested strongly at the polling site.

It is reported that on the day of the vote, the Indian House of Lords was forced to adjourn for 15 minutes, but the opposition MP’s behavior did not prevent the passage of the bill. Instead, the bill was not only passed quickly, but the eight rioting opposition legislators were suspended for a week for “malcompetence”.

In the ongoing peasant protests, opposition parties have expressed solidarity with farmers as an opportunity to weaken the power of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.

However, everyone’s opposition did not make Modi give in. According to the Associated Press, on the 17th local time, the Supreme Court of India hoped that the Indian government could consider delaying the implementation of the new agricultural reform law to calm the anger of protest farmers.

However, Modi refused in a speech to the protesting farmers in Madhya Pradesh on the 18th.

However, everyone’s opposition did not make Modi give in. According to the Associated Press, on the 17th local time, the Supreme Court of India hoped that the Indian government could consider delaying the implementation of the new agricultural reform law to calm the anger of protest farmers. However, Modi refused in a speech to the protesting farmers in Madhya Pradesh on the 18th.

The long-standing reform measures of the Indian government have not really improved the living standards of the Indian people, but have exacerbated the gap between rich and poor.

The introduction of the agricultural bill does not seem to take into account the actual situation of Indian farmers. Coupled with the intensification of the COVID-19 epidemic situation in India and the downward trend of the economy, the government’s proposed agricultural reform at this juncture has reduced the trust of the Indian people in the Modi government.

In the future, how to deal with the contradiction between reform, development and stability in a state of already high distrust between the government and the people will remain a major challenge facing India.