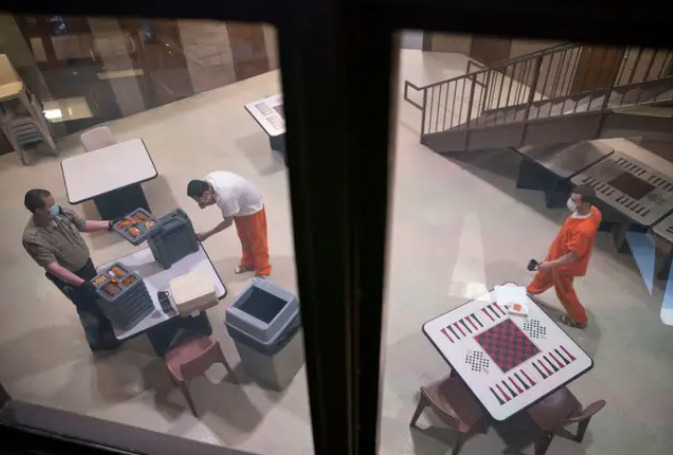

Overseas Network, February 9 Recently, Liz Oyer, a public defender of the United States, published a commentary article on Buzzfeed News Network, telling his own experience about the bad situation faced by prisoners after the outbreak of the pandemic in the U.S. prison system.

She said that the novel coronavirus spread like wildfire in detention centers, and quarantined prisoners were inhumanized and handcuffed to bed for 13 days.

The full text is excerpted as follows:

As a public defender in the United States, my job is to defend the poor accused of crimes.

I have a lot of clients in prison, but after the outbreak of COVID-19, we have been blocked by a high wall.

Before the pandemic, I visited incarcerated clients several times a week, provided support in court, and actively handled their cases. But when the coronavirus outbreak broke out, my legal work stopped abruptly.

The visiting prison was suddenly interrupted and the court was closed. My clients were basically quarantined in prison while I was staying home with my family. I feel like I left in a lifeboat, while the others were trapped on the boat and waiting to sink.

None of my clients immediately got sick. At first, “isodepartment” may keep them safe. However, staff enter and exit the prison every day, so it is only a matter of time before the COVID-19 invasion.

When the virus first hit a pretrial detention center in the spring, it spread like wildfire in a crowded place, and my client was trapped in this “fire building”.

Everything I learned from my practice of three years in law school and 15 years after that suddenly became useless. I filed one motion after another to try to get people out of prison, but it didn’t work very well.

Another “22 military rules” have been formed in the U.S. prison system during the pandemic: If there is no coronavirus in an institution, prisoners in the institution are considered ineligible for release because the health threats they face are not urgent enough.

And prisoners in outbreak institutions are also considered unsafe and unable to be released, because they may bring COVID-19 to the community.

Since then, more and more clients have been sick. In June 2020, Allen, a 43-year-old, healthy client of mine, was tested for COVID-19 in a Baltimore prison. He was sent to the city of Hagerstown for quarantine without any symptoms.

There, Allen and other prisoners who tested positive were quarantined in a tent. Allen was handcuffed in the bed in the tent for 13 days. He doesn’t have a place to shower and is not even allowed to call his family to tell them that he is still alive.

I didn’t exaggerate how much pressure this period has brought to the families of prisoners. Visits were suspended and prisons were suddenly closed, limiting contact with the outside world.

Their family members have been imagining the worst of the situation for days, even weeks.

In October 2020, just as my other client, Robert, was nearing the end of his sentence at federal prison in Fort Dixburg, New Jersey, his roommate was diagnosed with COVID-19.

The prison staff sent the patient back to the dormitory for six people, and he slept in the upper and lower bunks with Robert. These people are required to go to bed from morning to night to reduce the possibility of spreading the virus.

A few days later, when the prison finally tested others, it was found that everyone had contracted the novel coronavirus. Not surprisingly, this is just the beginning of a larger pandemic: nearly 1,500 of the 2,500 prisoners in this prison are now diagnosed with COVID-19.

If a nursing home or hospital deals with the outbreak this way, criminal investigations will follow. But when the lives of prisoners are threatened, the United States seems to be satisfied with adopting lower standards.

In early February, after five months and submitting eight court documents, I finally got a “sympathetic release” for one client. He is 36 years old and has advanced kidney failure. A doctor told the court that he could die if he contracted the novel coronavirus.

I was going to pick him up from the North Carolina prison, but before I arrived, the prison administration took him to a bus that took 10 hours to drive, at a time of COVID-19.

Prisons are the uncontrolled breeding ground of COVID-19. There are many of my clients in the federal pretrial detention facility in Baltimore, and since January 2021, one third of the people here have tested positive for COVID-19.

The facility is now busy taking some basic preventive measures that should have been taken a few months ago. While Maryland has prioritized vaccinations for residents of nursing homes and other gathering places, it has not provided vaccines to my clients, who are also at risk.

The United States has tools to protect prisoners, including compassionate release, leniency, etc. Now there is a vaccine. The United States must use these tools without reservation, otherwise it will be judged harshly by history.