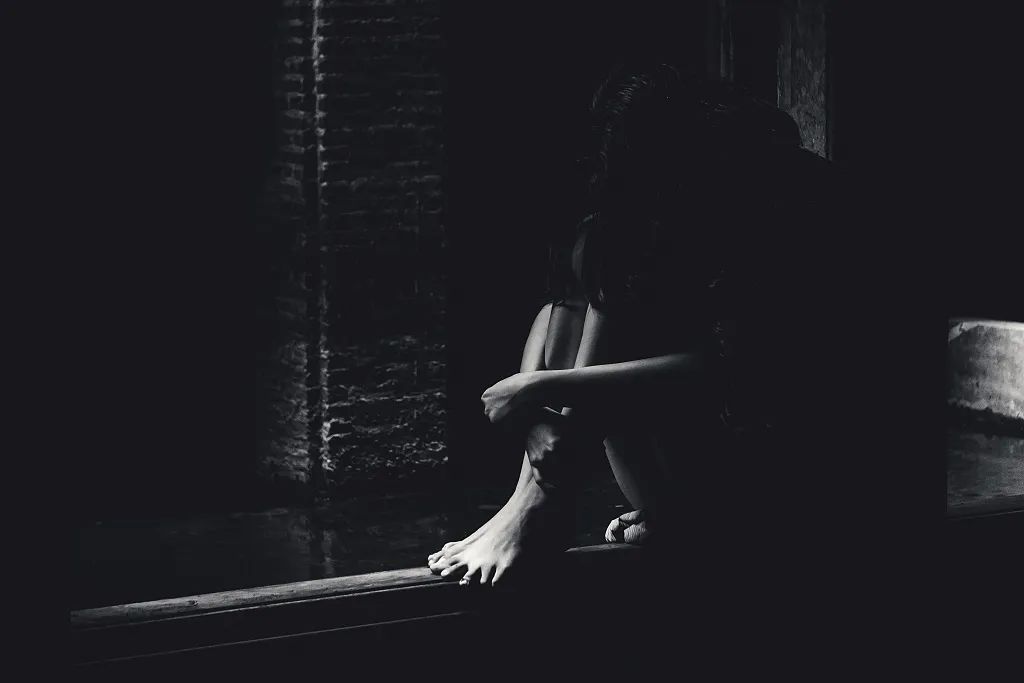

Sexual assault has always been a big problem in the U.S. military.

In fiscal year 2019 alone, the U.S. military received 7,825 reports of sexual assault involving military service members, and 4,834 completed investigations involved 5,245 victims and 5,140 respondents.

Women account for more than 80% of the victims, but about 1,000 men also reported sexual assault.

A previous study also showed that more than 80% of the U.S. military personnel with sexual minorities have experienced sexual harassment, and one third have been stalked and sexually assaulted.

According to the United.S. Department of Defense’s official report in the fiscal year 2019, US. The military service received 7,825 reports of sexual assault involving armed forces as Either victims or subjects.

The report says that the 4,834 completed investigations involved 5,245 victims and 5,140 subjects. The data shows that women are more than 80% of the victims, but about 1-2 men also rep Orted sexual assaults.

Are these exposed events the whole?

The exposed sexual assaults are just the tip of the iceberg in all areas of today’s society, including the army.

To understand the total number of victims of sexual assault in the U.S. military, including those who choose not to report, every two years, the U.S. Department of Defense estimates the total number of victims of sexual assault in the past year through an anonymous questionnaire.

Not surprisingly, the total number of real victims is much more than what is currently revealed.

The latest survey in fiscal year 2018 estimates that more than 20,000 members of the army were sexually assaulted during the year, indicating that only 30% of the total incidents exposed through victim reports may be reported.

Not surprisingly, the total number is believed to be much higher than the reported one.

In the official report of the Pentagon in 2019, it shows that the latest s The Pentagon conducted a urve for 2018 FY estimates that over 2000 military members are exp.

Errenced sexual assault, suggesting that the reported incidents may only account for about 30 percent. The total.

The handling of sexual assault in the U.S. military is heinous.

Marta McSally is a senator and a veteran – the first female pilot of the United States Air Force to participate in the battle.

At a congressional hearing in 2019 on military sexual assault, she revealed her past experience:

“I was also a survivor of the military neutral assault, but unlike many brave survivors, I didn’t report what happened to me at that time.”

“Like you, I’m also a military sexual assault survivor.

But unlike many brave survivors, I didn’t report being sexually assaulted.”

“Once, I was caught and raped by a superior officer.”

“In one case, I was preyed and then raped by a superior officer.”

“I didn’t believe in the processing mechanism within the military at the time.”

“I didn’t trust the system.”

“Like many victims, I feel like this mechanism raped me again.”

“Like many victims, I felt like this system was raping me again.”

After many years of confising his heart, it was a relief for McSally.

But many U.S. military service personnel with similar experience are not so lucky.

Last year, twenty-year-old U.S. Army expert Vanessa Gillen died last year after telling his mother that she had been sexually harassed by a non-commissioned officer.

According to her mother’s recollection, Gillen did not report the matter to the authorities.

Gillen said, “They won’t believe me.”

She said, “They won’t believe me.”

What prompted Gillan not to report her experience? If she had reported it at that time, would justice have come?

Let’s take a look at another incident.

In the same situation, Kayla Knight chose the report.

In June 2013, she was sexually assaulted while working as an Army nurse.

Soon after, in early August, she submitted a report on the incident, and then the criminal investigation was officially launched.

However, in the next few years, she was greeted by multiple transfers, negative police assessment reports, and the eventual withdrawal of the case.

However, in the following years, she was subjected to numerous transfers, and a negative officer evaluation ation report, and the eventual dropping of the case.

Yes, she reported. However, since then, her life and career have never been back to the past.

Like Mesaally, many people did not say what they had been sexually assaulted at that time, because they had long been desperate for the internal processing mechanism of the army, and they chose to try to let time dilute those memories and pains.

And for those who chose to report like Kyra, they never thought that such an end was waiting for them.

Many people don’t speak about sexual assault, like McSally, because they are so disillusioned.

The military system and they chose to try to let time wash away memories and pains.

Those who did report, like Kayla, had hoped for a better.

These painful experiences are not limited to the United States.

In Canada, the United Kingdom, Israel, South Korea and many other places, a large number of men and women who are serving and have been discharged from the army face the same nightmare.

When will justice come? What kind of reform does the army need?