After Trump supporters attacked the U.S. Congress that was certifying the election results on January 6, the technology giants in Silicon Valley decided to punish the still-in-coming U.S. President.

Facebook and Instagram will suspend Trump accounts for at least two weeks until Biden takes office on January 20; Google’s YouTube will also suspend the publishing rights of Trump channel for one week; and Twitter will be more resolute: directly and permanently ban 88 million Fan Trump personal account @realDonaldTrump and further “chased” his team account and deleted Trump’s tweets on the official presidential account.

So far, more than 10 social media platforms have permanently or temporarily blocked Trump’s accounts or restricted the dissemination of relevant content.

When conservative voters turned to Parler, a social media application that flaunted unsupervisory remarks, it was immediately removed from the app store by Google and Apple, and was canceled by Amazon for server support. It ceased operation from January 11.

Many liberal users cheered and thanked Twitter for finally completing a “good thing” they should have done long ago.

However, there are also concerns that these technology giants with hundreds of millions of social media users have too much power, and the process of blocking accounts is not transparent enough to interfere with freedom of expression on the Internet.

German Chancellor Merkel, who is far away in Europe, also said that Twitter’s approach is “problematic”.

She did not defend Trump, but stressed that the relevant laws to ban social media accounts should be made by the government and should not be under the sole control of private companies.

This online block of Trump leaves too many questions: Is the social media ban reasonable and legal? What role did these platforms play in the congressional riots? Should the platform restrict dangerous speech? Why are Trump and conservatives insisting on repealing a “Article 230” to revenge on social media? How will the Democratic-controlled U.S. Congress treat the technology giants under antitrust investigation in the future?

Is the ban reasonable and legal?

One of the most popular debates after Twitter announced the ban is: Is this a violation of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which focuses on “protecting freedom of speech”?

The amendment states: “Congress shall not enact laws concerning the establishment of the state religion or the prohibition of religious freedom; the denial of freedom of expression or the press; or the denial of the right of people to peaceful assembly and petition the government.” That is to say, the target of the law is Congress or the United States government, not private companies.

Gregory Magarian, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis who studies the U.S. Constitution, told Interface News that Twitter’s ban on Trump accounts, as well as other restrictions on social media platforms, do not violate the First Amendment, which only protects speech from Affected by government actions.

“Social media companies do restrict freedom of speech, and the question is whether those restrictions are justified,” Magrian said.

Mike Horning, director of social informatics research at the Center for Human-Computer Interaction of Virginia Tech University, believes that it is difficult for Americans to reach agreement on reasonable issues.

“While these acts are legitimate in the United States, they do cause many Americans to worry,” Horning told Jiemian News. “Most people value the principle of free speech.

Even if companies can restrict it, they want to see open forms of communication. The permanent ban may be considered by many to be anti-democratic in principle (measures).”

Jack Dorsey, CEO of Twitter, tweeted on January 14 that he was not glad or proud of the closure of Trump’s account, but believed that it was the right decision.

Dorsey admitted that the move would have a negative impact on the open and free Internet, but it was a business decision made by the company to adjust itself, non-governmental.

Facebook CEO Zuckerberg said in the middle of last year that he did not think the platform should act as an “arbiter of all truths”. However, Facebook still deleted false information from Trump’s account last August and banned Trump’s account for at least two weeks after Congress confirmed that Biden was elected president.

But in Magrian’s view, the reasons for restrictions given by social media platforms are sufficient:

Disinformation is a serious problem in the United States and around the world, such as Trump’s false claim that there is a sinister conspiracy to steal his election results.

The same is true of extremeization and planning of violence.

These problems pose a threat at present because social media makes it easier to spread false information and plan violence.

When social media companies try to stop these threats, they are acting in a socially responsible way.

Should the platform restrict dangerous speech?

Although Twitter and Facebook have made Trump’s opponents dream come true, these big platforms have actually made each other dissatisfied.

As early as the 2016 election cycle, social media platforms represented by Facebook were called a key role in “Russia”.

According to the U.S. intelligence agency, the misleading information spread by countless false accounts on the platform constitutes interference in the U.S. election.

In the following years, the number of users of social media platforms has steadily increased, but the control of extreme speech does not seem to be convinced. While active user Trump keeps making controversial remarks, Twitter believes that his tweets can be labeled with warnings but not deleted for public interest, which makes liberals very dissatisfied.

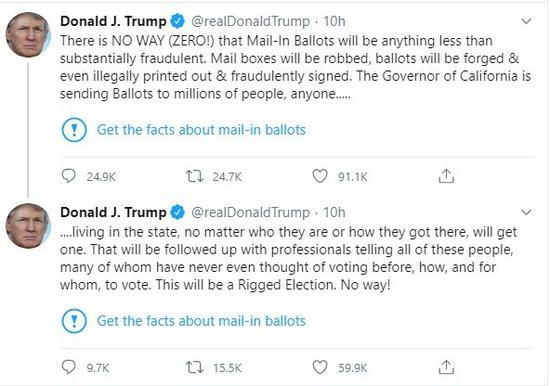

It wasn’t until May 2020 that Twitter first added fact-checking labels to content posted by Trump, which made unsubstantiated allegations of mail-in ballots.

Software Engineer Timothy Aveni’s job is to prevent the spread of misinformation on Facebook platforms.

“President Trump has been an exception to Facebook’s ‘community standard’ for years; he’s been releasing hateful, targeted messages again and again and again…

He’s allowed to break the rules because of the ‘news value’ of his political speeches,” he said when he resigned in anger in June.

When more and more opposition appeared, Zuckerberg compromised and announced that the company would take several steps to combat hate speech.

However, the domino effect has been triggered, and many big companies have promised to suspend advertising spending on Facebook in an attempt to force the company to intensify its efforts to crack down on hate speech and false information.

These major customers include American telecom operator Verizon, European fast-moving consumer giant Unilever, Coca-Cola, Honda and so on.

In the eyes of many, Trump’s privilege as President of the United States, as well as the inadequate regulation of dangerous speech on social media, indirectly encouraging some extremists to gather and spreading conspiracy theories or separatist remarks, contributed to some extent to the impact on the Capitol.

Magrian believes that social media companies have not done enough before to limit dangerous speech on their platforms.

While they are careful not to restrict free speech, tech companies are long overdue to do their best in their technological capabilities to ban conspiracy theoretic group QAnon, anti-vaccine extremists, and others who provide disinformation and violence.

Twitter should do more and label many Trump’s tweets falsely earlier.

Unfortunately, the terrorist attacks on the Capitol have become the only way to make social media companies aware of the seriousness of the problem.

As for the privileges enjoyed by the president, Magrian stressed that the president’s remarks are important because he is very powerful. On the other hand, it also means that his speech can cause more harm.

This paradox poses a challenge to social media companies. The platform may tend to impose more restrictions on the words of leaders, because these leaders, especially the president, can always find ways to convey their message to the public.

“Twitter’s ban on Trump hurt him because Twitter is everything Trump knows. A more skilled politician would easily resort to other methods, such as press conferences, to convey his message.”

How to define platform immunity?

Long after his tweets were labeled with warnings, Trump used the tools of revenge for Twitter: he signed an executive order to demand a retrial of section 230 of the U.S. Communications Regulatory Act, trying to repeal the widespread exemptions enjoyed by platforms.

The clause states: “The provider or user of the interactive computer service shall not be regarded as the publisher of third-party content.” It means that if a user posts illegal content on Twitter or Facebook, the platform will not be prosecuted.

These companies can set or relax or tighten censor standards for platform content.

If social media companies lose the legal protection provided by Section 230, they may delete more potentially problematic content to avoid more lawsuits.

At the same time, the second part of Article 230 of the Communications Regulatory Act also mentions that the provider or user of interactive computer services is not legally liable for restricting access to voluntary actions taken by the provider to deem obscene, dirty, excessively violent, harassing or other objectionable content.

For example, Facebook can block some conspiracy theories or incite violence and will not be prosecuted by content publishers.

However, after repealing Article 230, when the platform deletes a large number of controversial content, it may also provoke lawsuits. Regulators can claim that excessive deletion of posts on social media platforms is suppressing freedom of expression and deliberately curbing the spread of one party’s speech.

Trump’s executive order also sought to bring complaints about political bias to the Federal Trade Commission, which can investigate whether the content censorship policies of technology companies meet their commitment to neutrality.

Magrian stressed: “Most people who know how to communicate online will agree that simply repealing Article 230 will turn into a disaster.

If tech companies are responsible for every bit of harm they spread, online communication is actually less realistic.”

But in order to better hold social media platforms accountable, Magrian believes that exceptions can be created on Article 230.

Similar to copyright management, the network platform should delete potentially infringing content at the request of the copyright owner.

The government can use similar measures to reasonably hold social media platforms responsible for deleting more dangerous remarks.

In response to Congressional regulation of social media platforms, Horning pointed out that Congress should be careful when drafting laws that it will not violate the First Amendment.

This will also be the tricky point in drafting legislation. Future policies are likely to strike a balance between public interest in open communication and ensuring public safety.

“To be fair, Congress providing more guidance on how social media can choose between what is considered acceptable and unacceptable discussions may reduce the burden on social media companies,” Horning said.

Amy Bruckman, a professor at the School of Interactive Computing at Georgia Tech, believes that creating more value-driven small non-profit platforms is another way to make the social media environment better, so that people can choose the website that suits them.

She told Interface News: “Big media platforms are making money from sharing hate speech, which encourages them to promote hate speech more. These large websites are designed by the desire to maximize advertising revenue

But nonprofit websites can think about what kind of world they’re helping to create and make decisions based on a vision of contributing to the public good.

We need to provide public funding for many non-profit websites and set content standards for all websites created through a transparent and democratic process.”

How does Europe regulate technology giants?

The social media blockade led by Twitter has caused waves in Europe.

While the United States empowers private companies on the basis of the First Amendment, the other side of the Atlantic is initiating the strictest regulation of technology giants.

German Chancellor Merkel’s chief spokesman Steffen Seibert said at a press conference on January 11 that “Merckel believes that there is a problem in completely closing the account of an elected president.” Rights like freedom of speech “can be subject to interference by law, but within the framework prescribed by the legislature – not by the decisions of the company.”

Merkel’s position echoed by French Finance Minister Le Maier, who said that it was the state, not the “digital oligarch”, who was responsible for regulation, and that large technology companies were one of the “threats” to democracy.

Matt Hancock, the former UK’s Culture Secretary (now Health Secretary), said the move showed that Twitter had “made an editorial decision” that would raise questions about their editorial judgment and regulation, implying the fact that social media companies are no longer just platforms.

Dr. Julian Jaursch, an expert at the Stiftung Neue Verantwortung, a think tank for digital technology and social development in Berlin, Germany, believes that large-scale technology level of providing cyber information space The debate over the role of Taiwan has been on the academic and civil society for many years, but now it is on the political agenda.

He pointed out to Interface News that one of the problems that need to be solved is what power should be left to private enterprises in regulating speech.

In some cases, politicians have called for more content reviews on the platform, such as when dealing with illegal content. But it may also be beyond everyone’s consensus, just like the doubts caused by blocking Trump.

Jörsch believes that political leaders can sometimes be exempt from platform rules because their information is in the public interest.

But at the same time, the platform also said that no one can be out of politics, including world leaders.

“The question becomes who decides these situations, what its guiding principles are, and how to appeal the decision.

All these questions are currently given by the platform.

But like the Digital Services Act, it would be preferable to reach a more consistent standard after external expert review,” said Jölsch.

In mid-December 2020, the EU submitted two draft bills aimed at limiting technology giants, the Digital Market Act, which aims to address unfair competition in the industry, and the Digital Services Act, which imposes more responsibility for illegal behavior on their platforms.

The Digital Services Act is primarily aimed at social media platforms with more than 45 million users in Europe. It stipulates that these social media have the obligation to review and limit the dissemination of illegal content.

Failure to comply will be regarded as a violation. Illegal content includes: terrorist propaganda, child sexual abuse materials, use of robots to manipulate elections, dissemination of harmful speech to public health, etc.

In 2018, the European Union also passed the landmark General Data Protection Act (GDPR), which is regarded as the “most stringent” legislation in the field of privacy protection, greatly raising the requirements for how consumers’ data is stored and shared.

Georgia Tech professor Lakman on the forthcoming new book Should You Trust Wikipedia? The Network Community Design and Knowledge Building states: “You should not review statements you disagree with, but refute them with other statements.

In fact, this has evolved into ‘the government can’t censor opinions, but private companies can.’ We didn’t block the censorship, but devolved power.

I think the United States should turn to more European-style speech regulations, with democratically elected representatives debating the criteria for possible speech.”

Does the Democratic government want anti-monopoly liquidation?

Tech giants face more trouble in the face of the incoming Biden administration and the Democratic-controlled House of Congress.

James Grimmelmann, a professor of digital and information law at Cornell University, told Interface News that under the Biden administration, an antitrust liquidation against large technology companies is coming.

“The Biden administration will abandon the Trump administration’s misleading focus on political ‘neutrality’ (which is actually pushing businesses toward conservatives) and focus on the excessive economic power that tech companies enjoy,” said Grimmelman, a former programmer at Microsoft.

Last July, the Democratic-led House held an antitrust hearing to investigate the monopoly allegations of four technology giants, including Facebook, Apple, Amazon and Alphabet, Google’s parent company.

Among them, Apple and Amazon face similar questions, that is, whether they abuse the power of market “gatekeepers” to deprive other companies on the platform of their interests; Facebook and Google face accusations of achieving dominance in the field of social media and search by squeezing out or acquiring competitors.

As of January 16, these companies, together with Microsoft and Tesla, constitute the six most listed companies in the United States by market capitalization.

Last December, the U.S. government also formally sued Facebook with 48 states and territories, accusing it of abusing market power in social networks to suppress smaller competitors.

Attorneys general in as many as 38 other states said that Google violated antitrust laws in the online search and search advertising market.

In addition to advancing antitrust investigations, promoting federal privacy laws is also an important topic for the U.S. government.

Jölsch pointed out that this will provide some rules and guidelines for companies to process user data, which is at the core of their business model.

During the 2016 presidential election, Cambridge Analytica, a political data company, illegally collected data from millions of Facebook users and accurately put a large number of political advertisements.

But this scandal that made social platforms the target of public criticism did not actually bring about the expected changes. After the scandal was exposed, there were voices in American politics to promote federal data privacy laws. But today, more than two years later, except for a few state laws, Americans’ “privacy” is largely in the hands of major companies.

Hornen pointed out that Democrats in the United States tend to focus on data collection practices and how social media use this information.

They may see policies to impose more protection on citizens’ data, and there will also be policies that require social media companies to improve transparency.

Regarding the content management triggered by the blocking of Trump, Horning said: “Historically, American policies have been trying to encourage more speech, not less speech.

Social media is indeed the most modern form of public communication in our time, and the policies formulated in the next few years will determine whether this will remain the direction for the United States to move forward in the digital age.”